Learning from Environmental Design: Waltham Forest College

Waltham Forest College ©Studio DERA 2026

Words by Matthew Feitelberg, Sustainability Consultant and Architect, Love Design Studio

Whether we realise it or not, buildings are among the most influential teachers we encounter.

In schools especially, environmental design quietly shapes patterns of attention, comfort, and behaviour. While classes and curricula may explain climate in abstract terms, it is the building itself that communicates what environmental responsibility feels like in practice.

As such, when considering schools, environmental design carries a responsibility beyond performance and technical compliance, ensuring internal conditions support comfort, concentration, and health. The school is a place where thermal performance, air quality, daylight, acoustics, and energy use cannot be seen as separate entities, but are interdependent conditions that shape how learning takes place. When Love Design Studio was appointed to work with Studio Dera Architects on the sustainability aspects of the newly proposed engineering building at Waltham Forest College in 2024, it was this philosophy that guided the design team, using each element as an opportunity for observation and understanding, allowing the building itself to participate in the educational process.

Cultivating Environmentalism

Located in the London Borough of Waltham Forest, the new engineering building at Waltham Forest College was conceived as more than a replacement for an outdated teaching space. Developed as part of a wider ambition to decarbonise the college estate and respond to increasing climate pressures on educational buildings, the design had, at its core, concerns about energy use, thermal comfort, materiality, and long-term adaptability. From the outset, the building was understood not only as an object to be optimised against environmental targets, but as a setting in which students would encounter the consequences of environmental decision making.

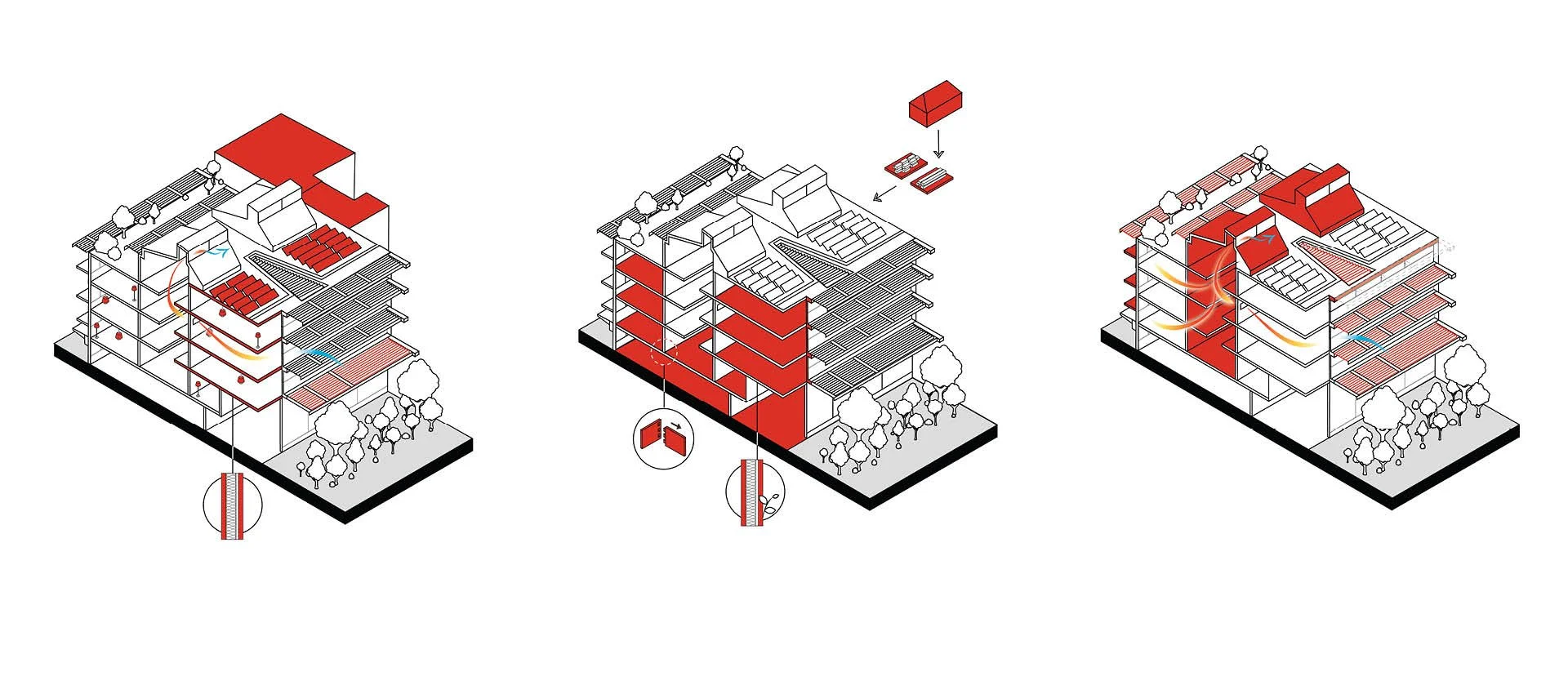

Illustrations showing strategies for energy, materiality and overheating © Love Design Studio

A key challenge for the design team was balancing the goal of making environmental design visible with the need to adhere to planning systems that prioritise compliance, an issue our ancient ancestors did not face.

Planning authorities and professional institutions must, by necessity, imagine the environment as a fixed system so that compliance can be judged consistently, reliably, and quantitatively. [1] This is system is supported by an increasing number of guidance documents published by institutions such as the GLA, CIBSE, RIBA, LETI, the UKGBC, BREEAM, and Passivhaus. They are usually user friendly, easy to understand, and present numbers that designers should aim to meet in order to build a sustainable building, a process that, despite its flaws, has resulted in a more sustainable built environment. However, the desire to reach a single, all encompassing number in order to prove worth and ‘sustainability’ can result in a static, single directional design process that forgets the building itself in pursuit of meeting tick box exercises, accreditation, and acclaim.

For example, as a requirement of the GLA, most large developments are required to submit an environmental and sustainability statement (ESS), a slightly tedious planning document that usually explains how the proposed development will address the London Plan policies that relate to the environment and sustainability. Initially, the plan for Waltham Forest College was to deliver this style of document; instead, what was eventually submitted was an encyclopaedia of the proposal’s environmental life, translating policy into understandable and teachable physical adaptation methods.

This decision was based on Love Design Studio’s past experience on working with schools and green skills fairs, and our realisation that handing the baton of sustainability to the next generation should start long before students transition to a professional environment. Furthermore, the need for healthy learning environments and progressive schools aligns with Love Design Studio’s raison d’être; improving spaces for people.

In an educational setting, environmental design carries a responsibility beyond performance alone. Schools are not neutral zones for learning, they are formative theatres in which patterns of behaviour, attention, and curiosity are rehearsed and performed. Thermal comfort affects concentration, air quality influences alertness, and access to daylight shapes circadian rhythms, all well documented and all measurable. However, schools also shape something harder to quantify, a student’s understanding of how buildings work, and, by extension, how the world around them in constructed and sustained.

During the design process and preparation for submission of planning for Waltham Forest College, the underlying principle was always to design a building that was as sustainable as possible. Our scope, which included whole life-cycle carbon, circular economy, overheating, energy, biodiversity, and air quality, could easily have been pieced together to become a standard ESS. However, the desire from both the school and the design team was to offer something more, giving students the opportunity to learn from the building that they would be learning in.

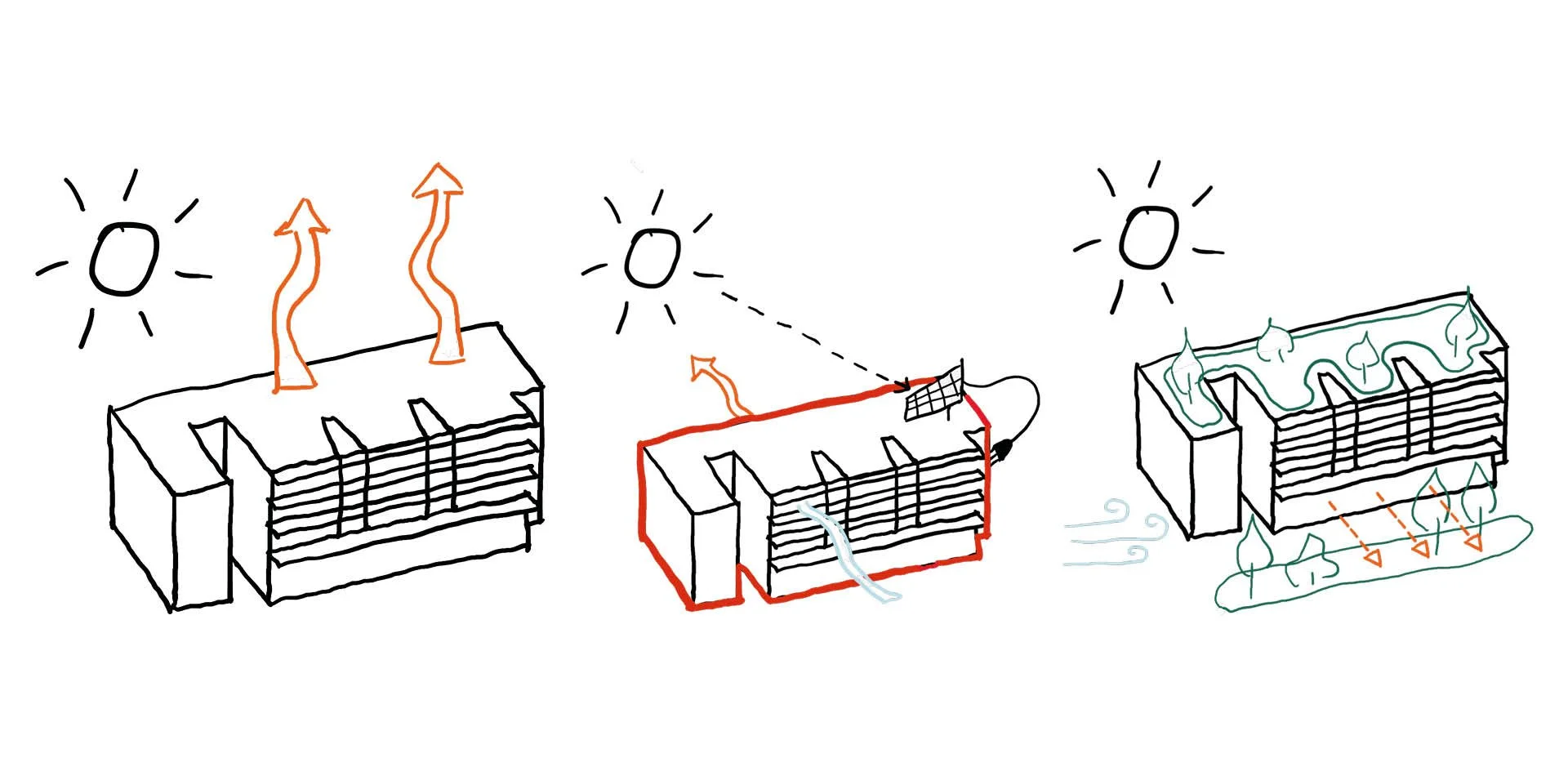

Initial design sketches © Love Design Studio

Sustainable Voyeurism

Too often, high-performing environmental strategies are concealed behind suspended ceilings and plasterboard walls, rendering sustainability a somewhat abstract concept, more defined by what is visible; solar panels, wind turbines, timber columns, etc. For the design of the new engineering building, it was decided that students should be able to learn from every environmental decision that was made, whether that be material choice, window openings, or air flow decisions. Instead of being treated as background infrastructure, environmental systems were designed to be visible, intelligible components of the architecture.

Aerial view ©Studio DERA 2026

Bio-based materials are proposed to be on display throughout the construction, not just in the form of a timber structure, but through exposing natural insulation through vision panels within circulation areas, allowing students to see, quite literally, what low carbon construction looks like. Ventilation strategies were expressed physically through operable panels in façade and atrium whose movement could be observed and felt, connecting cause to effect as windows opened, air moved, and temperatures shift.

Perhaps the greatest challenge was combatting overheating, a common problem in most schools. Through successive rounds of simulation and design refinement, a strategy was eventually developed that included climbing plants, large swaths of brise soleil, deep window reveals, and strategic ventilation openings. This resulted in a design which seamlessly blended highly evolved environmental design with the architectural language of the building.

In doing all of this, the building itself becomes a teaching apparatus. Decisions typically confined to spreadsheets and simulation outputs are translated into spatial experiences that students can occupy, question, criticise, and critique. Environmental design thus operates on two registers simultaneously; maintaining internal conditions required for learning while also exposing the mechanisms by which those conditions are achieved. The school therefore does not simply perform sustainably, it explains itself as well.

This approach acknowledges a simple but powerful truth, the next generation will inherit a climate that demands literacy as much as innovation. By allowing students to observe and engage with the building’s environmental logic, the new engineering building treats sustainability not as a target achieved at handover, but as a conversation continued over decades, becoming guardians of environmental knowledge through their bricks and mortar.

The project was submitted for planning in 2025.

References

Evaluating sustainable building assessment systems: a comparative analysis of GBRS and WBLCA, Anyana et al, 2025.