Learning from Environmental Design: Resilience and the Human Experience

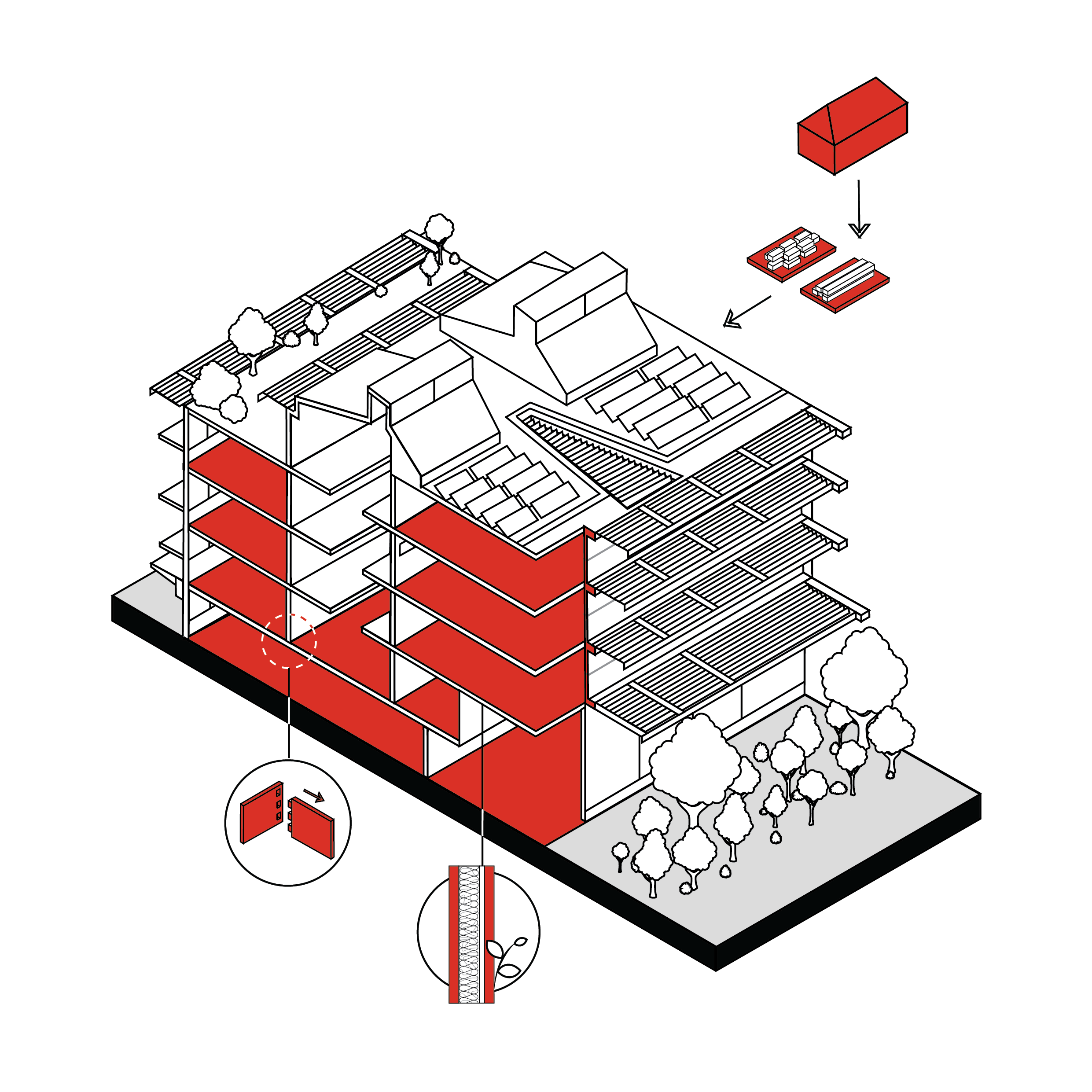

Diagram, Waltham Forest College © Love Design Studio

Words by Matthew Feitelberg, Sustainability Consultant and Architect, Love Design Studio

What was your school like? Take a moment and try and remember. Close your eyes if you have to. Was it ever too cold? Or maybe too hot? How long did it take you to cool down after playing football at lunch?

Personally, I remember how unbearable the final weeks of school were before summer holidays. Looking back, I’m sure that some of my discomfort stemmed from the impending freedom of summer, yet the dominant memory is a kind of malaise; sitting in a hot, stuffy, airless room with inoperable windows in a poly-blend uniform.

These memories, however disparate and fragmented, form part of a greater truth that buildings shape our memories, moulding the way our bodies understand the climate around us.

Today, these experiences can be understood through the lens of environmental design, a discipline concerned with shaping buildings that support comfort, health, and attention while minimising energy consumption and environmental harm. At its core, environmental design seeks to align the design of buildings with human physiology through the regulation and manipulation of light, air, temperature, and aesthetics. However, environmental design is far from a modern invention; what feels like a personal memory is part of a far longer design tradition of living beings deliberately shaping the world around them.

This two part series will explore how environmental design is far more than a technical discipline, it is a social exercise shaped by memory, culture, and climate, mediating the relationship between human physiology the natural world.

This first article begins by tracing the history of design from instinctive shelter to mechanised interior, asking how buildings have shaped our understanding of comfort and weather before going on to look at how architecture can help to make this environmental logic legible, experiential, and teachable.

Part two explores how this concept was put into practice at Waltham Forest College, a project we worked on alongside Studio Dera Architects.

In Pursuit of Protection

Environmental design as we understand it today would have, for most of history, been considered a fundamental but standard part of construction; the simple shared instinct of species who construct their own environment in pursuit of protection. This instinct, to protect oneself from the weather, is seen across the animal kingdom; think beehives, bird nests, or the underground citadels constructed by ants, all of these ultimately serve the same purpose, to protect.

Human shelters, on the other hand, have developed into something far more consequential, constructed on a scale and complexity no ant could ever imagine. Yet for all their grandeur, our buildings are still fundamentally tethered to something remarkably simple; the comforts of the human body.

Despite our geographic range, our bodies remain relatively conservative in its demands. When accounting for regional variations in comfort, most people feel comfortable at a temperature of between 19° and 28° Celsius, a constraint which has quietly shaped the built environment. [1] Architecture has thus been tasked with a simple brief; ensure internal stability despite external variability. Environmental design therefore becomes the mechanism by which this tension is resolved, balancing fabric, form, and systems in a continuous negotiation.

The history of the built environment tells the story of designers harnessing their knowledge of the local environment to provide internal comfort. For example, windcatchers have been used for thousands of years to cool and ventilate buildings in hot and arid climates across the Middle East, while in Classical Greece, architects oriented buildings to take advantage of the seasonal locations of the sun, capturing solar energy in the winter while shading the interior in the summer.

As technology developed, the need to design buildings around the vagrancies of the weather was eliminated.

Too hot? Put on the air conditioning. Too cold? Put on the heating. Stuffy? Turn on the fan.

Buildings became areas of escape, sealed off and disconnected from the environment. We now understand what the overall result of this development has been, as climate change presents arguably the greatest existential crisis faced by humanity. But I would argue there is another, more insidious consequence of this transition; we have lost our innate understanding of the natural world, forgetting in a single generation what had been honed over millennia.

The New Vernacular

Even as we resurrect the knowledge of old in our modern construction methods, designers are increasingly confronted with a climate that has changed; seasonal boundaries have become increasingly blurred, average temperatures are rising, and historic weather patterns can no longer be relied upon. Vernacular building strategies are, by definition, finely turned to local weather patterns that in some cases no longer exist. They now struggle with prolonged heatwaves, warmer nights, and shifting occupancy patterns, rendering imitation without adaptation not only ineffective, but counterproductive.

As such, the modern construction project must move beyond revival of old ways and towards reinvention. Environmental design in the 21st Century is asked to operate simultaneously as science, art, and conscience; to predict future climate through dynamic simulation, to temper them with passive principles, and to commission mechanical systems only as a final safeguard rather than a habitual reflex. Logic alone is no longer sufficient. Everything must be quantified.

In this century, environmental design has reached a peak of technical sophistication and refinement, and, paradoxically, invisibility. Holding on to Modernist ideology that prioritises clean lines and surfaces and a clear separation between the outside and in, most contemporary examples hide their environmental choices behind roofs, walls, and floors, prioritising a high-tech approach to sustainability that relies increasingly on software and technology as opposed to human intervention.

Modern examples such as Bloomberg’s new headquarters in London demonstrate this duality. Although not an educational building, it’s hyper sustainable innovations allowed the design to achieve a near perfect design stage BREEAM rating. The building integrated strategies that significantly reduced energy consumption and water use, as well as an automated hybrid ventilation system that draws fresh air in through the iconic bronze fins that line the façade. However, much of this ingenuity is embedded in sensors and control systems that are hidden behind ceilings, within facades, or buried in mechanical plant rooms, making the building’s environmental logic opaque to occupants.

Environmental design has always relied on a tacit agreement between people and the climate. For much of history, that agreement was stable enough to be learned, refined, and passed down from building to building. Today, that stability no longer exists. Designers must work with climates that are shifting faster than precedent can respond, rendering both mechanised certainty and vernacular imitation insufficient on their own. Under these conditions, buildings, therefore, demand a new kind of response, one that treats buildings not as structures to be optimised, but as environments that can cultivate a new understanding.

If climatic stability can no longer be relied upon, then the spaces we inhabit must teach us how to adapt.

The implications of this shift become most visible in an educational setting, where buildings are uniquely positioned to function both as shelter and teacher. Addressing this tension requires more than improved standards or more efficient systems, it requires spaces that can reintroduce climate as something that is felt, understood, and questioned.

How Love Design Studio addresses this approach is explored in the second article in the series.

References:

Assessment of indoor thermal comfort temperature and related behavioural adaptations: a systematic review, Arsad et al, 2023

Predicting Comfort Temperature in Indonesia, an Initial Step to Reduce Cooling Energy Consumption, Karyano 2015

Analysis of thermal comfort in Lagos, Nigeria, Komolafe & Akingbade, 2004

Using the adaptive model of thermal comfort for obtaining indoor neutral temperature: Findings from a field study in Hyderabad, India, Indraganti, 2010